by Robert Cox

For the moment as western Europeans watch the nightly media display of Russian brutality in Ukraine, many instinctively feel it’s a long way away. An echo of British Premier Neville Chamberlain’s dismissal of Hitler’s threats to Czechoslovakia in 1938 as a “quarrel in a faraway country, between people of whom we know nothing.” One Czech emigrée saw the fatuousness of Chamberlain’s stance—Madeleine Albright. Balts and Poles, their memories fresh of Russian occupation, are clearly nervous. At greater distance, Portuguese, Greeks and Italians feel less threatened. French people show more concern with cost-of-living hikes—albeit driven by Russia’s actions. Yet the violence is happening on all Europeans’ doorstep. One false move, deliberate or careless, and NATO’s Article 5 activates. Perhaps. Let us look at the complexities of the context in which this war has come to pass.

Ukrainians suffer—bravely. Sadly, this will continue. Russians too are suffering. All Europeans to a degree are prisoners of today’s violence, war crimes, the war’s duration, the nagging unpredictability of its outcome. And this on top of the fragilizing Covid pandemic which is not over. Food and energy scarcities threaten. War-stoked inflation threatens welfare, jobs, and, for many, accustomed prosperity. With us too is the challenge of giving Ukrainians a prospect of something better than what Stanford historian Niall Ferguson called “the pity of war”. Europe’s biggest challenge since 1945 confronts citizens’ willingness to bear restrictions and challenges politicians’ imagination. Nor is it too early for the European Union to look ahead to the task of post-war rehabilitation.

We cannot predict the future. But to help us understand why we are here, let us take a look at Ukraine’s, Russia’s, and Europe’s crisis from different angles.

Russia: an Unwieldy Empire

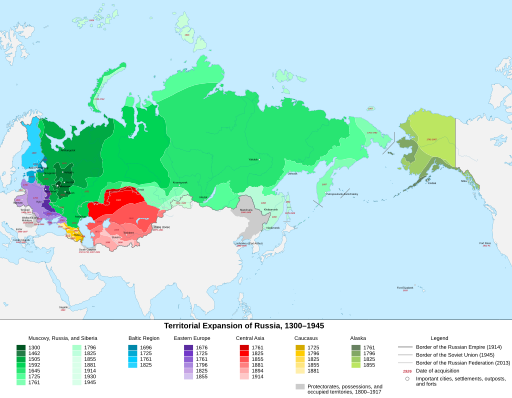

Your correspondent—an amateur Russian scholar and linguist – frequently focuses on the map of Russia. Behind Russia’s proclaimed security fears lies a deeper problem of demographics. Russia is a huge country. Over 11 time zones it covers 17 million square kilometers (km2). Seventy-seven percent of its population of 144 million people lives in European Russia west of the Urals—27 per km2. The European Union’s 447 million people occupy 4.23 million km2 – a population density of 118 per km2. Russia has the treble problem of governing a vast and often inhospitable space; containing a relatively small and diminishing population; mastering a poor economic basis and performance. On its western flank Russia faces a densely populated and concentrated space with a vigorous economy and rule of law—the European Union (EU). In the face of such imbalance Russia easily falls prey to an aggressiveness based on fear, if not paranoia. In this context consecutive Russian autocrats from Ivan IV to Vladimir Putin have sought to crush Russians’ freedom.

The conflict is also a war of information, or mis-information. Ambiguous love-hate sentiment towards “Europe” is old in Russia; Dostoyevsky and Solzhenitsyn are its prominent exponents. Migrant diasporas from Tsarist and Soviet rule, disillusioned and homesick, have heated antagonism towards the west. Germans, from Bismarck to Social Democrats (SPD), culminating in Chancellor Willi Brandt’s Ostpolitik that opened the way to German re-unification, have tried to “understand” and placate Russia. They are now less ready to give Russia the benefit of the doubt. History bequeaths a passionate and complex heritage of mutual perception, suspicion, incomprehension and fear.

The conflict is also a war of information, or mis-information. Ambiguous love-hate sentiment towards “Europe” is old in Russia; Dostoyevsky and Solzhenitsyn are its prominent exponents. Migrant diasporas from Tsarist and Soviet rule, disillusioned and homesick, have heated antagonism towards the west. Germans, from Bismarck to Social Democrats (SPD), culminating in Chancellor Willi Brandt’s Ostpolitik that opened the way to German re-unification, have tried to “understand” and placate Russia. They are now less ready to give Russia the benefit of the doubt. History bequeaths a passionate and complex heritage of mutual perception, suspicion, incomprehension and fear.

Ukraine – a Story of Identity

Lviv, chief city of western Ukraine, has changed names thrice over 150 years. The Austro-Hungarian Galician city of Lemberg became Polish Lvóv—then Russian Львов —before settling on its present name in Ukrainian. Such have been the shifting borders, sovereignties and identities of the region’s painful past and present. Ukraine was the ideological target of an essay published in July 2021 by Russia’s President Vladimir Putin. Putin devoted 5,356 words to challenge the concept of Ukraine’s separate identity. Ukrainians and Russians are the same people says Putin, as he rewrites history. Yet nowhere in this text are such words as gulag, kulak and holodomor (the great, organised famine of 1932-33 that cost 4 million Ukrainian lives), inflicted by Stalin. For Ukrainians these words are part of their identity. Many Russians believe their national identity is incomplete without Ukraine, the baptismal font of the 9-13th centuries of the Kievskaya Rus, the cradle of Russia. Now, into the vast Eurasian empire that is Russia, Ukraine sticks like a European wedge. So, potentially, does Belarus, were it to slide into the orbit of the West. Russia has chosen to see all this border zone as an existential threat.

Europe in Russia’s Mirror

Putin’s real grudge is less with further (unlikely) NATO eastward expansion, than with Ukraine’s political and economic drift towards the EU and away from Russia. Putin’s invasion has only strengthened the hypothesis, however remote, of Ukrainian membership of the EU. He has also, so far, succeeded in consolidating the EU rather than fragmenting it. Germany has thrown certain political inhibitions to the wind. Conventional wisdoms have been shaken. Hitherto staunchly neutral Finns and Swedes talk of NATO membership. Danes will vote on abandonment of their so-called “op-out” from EU defence and security cooperation. Until recently Poland objected vocally against a perceived threat of EU security ambitions undermining NATO’s role as Europe’s defender. Its tone is now softening. Numerous European countries now pledge to meet the 2% NATO GDP norm for defence spending. “The British public has been told for the last five years that the EU is a cumbersome, failing, slow organisation,” said Lord Peter Ricketts, a former UK national security adviser. “The EU has changed more in … four weeks than …. in the last 40 years of my career.” In early March EU leaders meeting in Versailles declared that Russia’s war in Ukraine has heralded a ‘tectonic shift in European history.’ We must now see how this evolves in practice.

Who Is in Charge?

In the growingly tense months of run-up to the Russian invasion it consistently appeared as if Moscow and Washington were orchestrating this European crisis over Europe’s head. This despite a flurry of European diplomatic activity of varying quality. The US paid lip-service to associating Europe with its initiatives. Russia was adamant that the EU had no role to play, thus betraying the depth of its animosity to the European Project as the EU likes to portray itself. Elsewhere in Europe the recklessness of the UK’s Brexit departure from the EU, in terms of European security, was further illustrated. Belarus meanwhile, to all intents and purposes, was swallowed into the maw of the Russian state.

Whose Alliance?

Whatever the outcome of Russia’s brutal invasion, with all its trampling on norms of civilised behaviour, two particular challenges face EU Europe. The urgent challenge is to strengthen what it calls its strategic autonomy. Essentially a French concept born of France’s reluctant partnership with NATO that its President Macron in 2000 called “brain dead” (Financial Times, November 7, 2019). European re-discovery of NATO’s virtues following Putin’s invasion is by no means sealed. Purchase by Germany, Belgium, and others of US-made F-35 aircraft rather than a French-led Eurojet alternative reveal the weakness of European defence procurement ambitions. Others, however, are less convinced of US commitment to the defence of Europe in the event of a Russian military incursion into EU territory. They look at the uncertain outcome of November’s US mid-term elections. They share American friends’ unease at the risk of a return of Trump to the White House. Biden does not convince them. And how would the folks back home in Wisconsin and Wyoming take to their boys defending Lviv or Berlin?

Mastering the Future

We want to assume that Russia will lose this war—albeit at what cost to all concerned? Whatever happens, the European Union will have to assume leadership in promoting a wider new security order in Europe while repairing the war damage, physical and political. A damaged Russia—if that is the outcome of today’s conflict—must not be left to sulk in its fastnesses, waiting for a chance for revenge. Further NATO expansion is not the answer. A reformulation of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation & Security in Europe (OSCE) might offer a framework for a buffer-zone of security, including Russia’s western military districts. The EU has no longer any excuse to delegate its security to a reluctant Washington, tired of more involvement in Europe anyhow. Political and economic reconstruction in the east is the EU’s responsibility. The EU did it with some success after 1990; the experience gained and instruments (such as the Bank for European Reconstruction and Development —BERD) are still there. Talented young Russians, now fleeing the country, and essential for its rehabilitation, must be encouraged to return home. As will Ukrainian refugees. This is not to exclude the US. EU and US officials are reportedly looking at erecting a transatlantic dialogue on Russia aimed at “giving a more permanent structure to the flurry of contacts that have taken place since the war in Ukraine” (Financial Times, March 30, 2202).

Meanwhile we must avoid certain traps. Sanctions and war losses may feed increasing unrest in Russia. Moscow’s grip on media may convince many Russians that western actions are responsible for their misery. Russia’s siloviki (strongmen) regime can suppress restless youth. More unpredictable might be the siloviki themselves if their nerves frazzle. Russia’s invasion may have been slower than planned but it has capacity for a long fight. Europe faces the struggle of persuading its own citizens that the economic and social burdens—including hosting refugees and cutting reliance on Russian oil and gas—are worth the cost and not soluble by a quick capitulation at the expense of the values that the European Union claims as its moral fundament.

On the Back Burner

Meanwhile Russia’s invasion has put a host of other issues on the West’s back burner. Issues that jointly concern the EU and the US and where they must foster mutual dialogue. Handling China is one such issue. The miserable early-April virtual summit between Brussels and Beijing demonstrated the nullity of any European illusions of an alternative partnership with China. Not that the more adversarial US approach gets us any further. Saving the wreckage of globalisation is another. Climate change cries out for urgent action – as the latest report of the Inter-Governmental Panel on Climate Change (IGPCC) demonstrates. Europeans faced with war-driven cost-of-living hikes will have less tolerance for what the EU calls its Green Deal. They are not alone. Energy exporters are starting to fear Green Deal success. This indeed is a component of Russia’s problem with existential fear. Already, forward-looking Russians—like Saudis and Iranians—are feeling increasingly uncomfortable with the prospect of a Green Deal success restricting even further elbow-room for management of their energy-export-dependent economies.

Meanwhile what the Russians are doing in Ukraine is criminal. Criminal against their own people too, who, under-informed, face even more hardship than they currently suffer. After decades of prosperity and welfare, Europeans are ill-prepared for this sort of thing. The political implications are enormous.![]()

Robert Cox, born in London in 1938, read economics, politics, German and Slavonic languages at Cambridge University and the College of Europe. He launched into journalism with The Economist in London, and later in central Africa. Cox then entered a second career with the European Commission, first in the Spokesman’s service, then in the private office of Commission Member, George Thomson. After a spell with the Development DG dealing with policy & economics and North-South dialogue development negotiations, he was appointed Head of the EC Mission in Turkey, where he experienced the 1980 military takeover. On return to Brussels he held senior policy and management posts with the EC information services. On the outbreak of civil war in Yugoslavia, Cox was detached to the EC Monitoring Mission in Zagreb. In 1992 he joined the new EC Humanitarian Office (ECHO) as its deputy head. Since retirement he has based himself in Brussels spending time painting, traveling and working on contemporary challenges facing the EU, notably with the think-tank Friends of Europe. He is married with two daughters and three grandchildren.